- Belgium

- France

-

Germany

- Italy

- Netherlands

- Poland

- Spain

- Sweden

- United Kingdom

Germany

A. Overview

Sector

SECTION A OVERVIEW

Updates:

Overhaul RStV links June 2020

ALM social media guidelines July 2020

New CE Code Oct 2020

Media treaties amends Dec 2020

Ad labelling online July 2021

CE Compendium December 2021

'Hypoallergenic' clarified (DE) Feb 2022

Ad labelling guidelines (EN) May 2022

Links refreshed September 2022

Sunscreen 'Reef friendly' claims U.S. Feb 2023

'Clean' marketing claims. U.S. May 2023

Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner/ Lex

Links reviewed Dec 2023; 4 links renewed

Revision of the EU Cosmetics Regulation

Obelis group March 11, 2024. EC pages here

Do Cosmeceuticals Really Work?

Potter Clarkson Jan 9, 2025

CONTEXT AND SCOPE

These pages cover the rules for marketing communications in the cosmetics sector. We don’t include labelling or packaging. A cosmetic product is defined here Definition ‘Any substance or mixture intended to be placed in contact with the external parts of the human body (epidermis, hair system, nails, lips and external genital organs) or with the teeth and the mucous membranes of the oral cavity with a view exclusively or mainly to cleaning them, perfuming them, changing their appearance, protecting them, keeping them in good condition or correcting body odours.’ (Art.2.1.a. Regulation 1223/2009). It may sometimes be unclear whether a product is a cosmetic within the definition, or whether it falls under other sectoral legislation. ‘Borderline products’ include medicines, medical devices, biocidal products, toys, foods and general products. The European Commission publishes here guidance documents to facilitate the application of EU legislation in these cases. This is a heavily regulated sector with requirements for e.g. the appointment of ‘responsible persons’ and the registering of PIFs (Product Information Files), which type of requirement is also outside the scope of this database.

COSMETICS MARCOMS RULES

There are two EU Regulations at the heart of the regulatory regime for the cosmetics sector, so all member states have those Regulations as the ‘core’ of rules. In the case of Germany, that core has some complementary national legislation but, unlike several other member states, there is no ‘Cosmetics Code‘ from the self-regulatory authorities (see point 3 below). The full picture is of four intertwined regulatory influences, as follows:

1. THE CPR AND COMMON CRITERIA

The Cosmetic Products Regulation (CPR) 1223/2009 deals largely with product formulation, the core marcoms-related provision being from article 20. 1: 'In the labelling, making available on the market and advertising of cosmetic products, text, names, trade marks, pictures and figurative or other signs shall not be used to imply that these products have characteristics or functions which they do not have'. In the same article, the EC is required to develop an 'action plan regarding claims used and fix priorities for determining common criteria justifying the use of a claim.' Full article here. The outcome was the ‘Regulation 655/2013 setting out under the Annex those ‘common criteria’ for the justification of claims for cosmetic products, i.e. the acceptability of a claim made on a cosmetic product is determined by its compliance with the common criteria. The six common criteria are:

Legal Compliance

Truthfulness

Evidential support

Honesty

Fairness

Informed decision-making

all extracted here with summary descriptions. These rules are directly applicable in member states. The (non legally binding) 2017 Technical document on cosmetic claims, provides guidance/ best practice for the application of Regulation 655/2013; Annex I sets out each of the six criteria and shows examples of claims that are not permitted. Annex II deals with Best practice for claim substantiation evidence and III and IV cover 'Free-from' and Hypoallergenic claims respectively. See also our following content section B.

2. NATIONAL LEGISLATION: COSMETICS

The Food, Commodities and Feed Code (EN) LFGB (DE) regulates cosmetic products nationally under Sections 26 and 27, the latter providing that product claims, information or designs/ presentation must not be misleading. A definition of a cosmetic product is in S.2 (5) LFGB that closely reflects the CPR definition (see scope above). In addition, the German Cosmetics Ordinance/ Regulation on Cosmetic Products KosmetikVerordnung (DE) regulates some national aspects that are not covered by the European Regulations, such as the labelling language, the labelling of non-prepacked cosmetics, notification procedures, and sanctioning. This regulation is used to monitor the movement of cosmetic products and the implementation of Regulation 1223/2009.

3. GENERAL MARCOMS RULES: ALL SECTORS

Legislation

The EU Directives on unfair B2C commercial practices 2005/29/EC and misleading and comparative advertising 2006/114/EC will also apply in parallel and without limitation to the advertising of cosmetics (recital 51 CPR and recital 5 Reg. 655/2013). The relevant provisions have been incorporated into German legislation in the form of the Act against Unfair Competition - Gesetz gegen den unlauteren Wettbewerb (UWG). An English translation Caveat The translation includes the amendment(s) to the Act by Article 4 of the Act of 17 February 2016. Translations may not be updated at the same time as the German legal provisions is available here; the 2006/114/EC Directive addresses business-to-business practices and protects traders from misleading advertising by others, setting down conditions for (fair) comparative advertising.

Self-regulation

Sectors such as cosmetics that 'enjoy' sector-specific rules from legislation also remain subject to general self-regulatory rules that apply to all sectors, which in the form of social responsibility/ taste and decency etc. are frequently applied in sector adjudications.

The German self-regulatory system has two SRO’s: The German Advertising Standards Council (Deutscher Werberat - DW), which deals with issues of social values and morality, safety and security, discrimination etc. via its Codes of Conduct (EN), and the Centre for Protection against Unfair Competition (Wettbewerbszentrale - WBZ), which is judicially authorised to prosecute unfair commercial practices; explanation of WBZ role here (EN).

The DW does not publish a cosmetics code; cosmetic marcoms should comply inter alia with the DW General Principles on Commercial Communications (EN), also known as ‘Ground Rules’ (grundregln), and the ‘Denigration and Discrimination’ Code (EN); WBZ provides an annual market report that includes a chapter on cosmetics with a review of the relevant cases and judgments (2013, 2014, and 2015 – EN; struggling to trace more recent reports; may now be members only). The WBZ also provides an overview of the advertising of cosmetic products here (EN) and updates of important cases are also included on the WBZ website; a collection of cases here (EN) has some significant findings on e.g. substantiation of claims. Some more ecent news is found with a 'Kosmetik' search on the WBZ website.

THE ICC CODE

In making rulings, DW include the ICC Advertising and Marketing Communications Code, here in English (2024) and here in German (2018 code), in its set of considerations, the others being applicable law and their own codes of conduct. Chapter D of the code covers environmental claims, which are relevant in the cosmetics context. Extracts are in our following content section B.

4. TRADE ASSOCIATIONS

Cosmetics Europe (CE) is a particularly active trade association, responsible for Guiding Principles on Responsible Advertising and Marketing Communication (2020 version). IKW (EN), the German Cosmetic, Toiletry, Perfumery and Detergent Association (Industrieverband Körperpflege- und Waschmittel e. V.), is the national trade association and a founding member of CE; all members commit to implement and uphold, in letter and in spirit, the CE guiding principles (as under s.1.5). IKW’s ‘explanation and comments’ on CPR is here (EN). Also valuable is the CE September 2020 Cosmetic Product Claims Compendium which assembles applicable legislation, self-regulation, best practices and guidance and the May 2019 Guidelines for cosmetic product claim substantiation.

SUNSCREEN PRODUCTS

How Do Consumers Interpret "Reef Friendly" Claims? Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz PC/ Lex. February 2023

The referenced judgements are from the U.S. courts

The EC pages on sunscreen products documentation and legislation are here

The EC Recommendation 2006/647/EC on the efficacy of sunscreen products and related claims, is non-binding but significant in the market. The Recommendation sets out examples of claims which should not be made for sunscreen products and outlines the criteria for minimum efficacy and procedures for substantiating claims

- No claim Definition ‘Claim’ means any statement regarding the characteristics of a sunscreen product in the form of text, names, trade marks, pictures and figurative or other signs used in the labelling, putting up for sale and advertising of sunscreen products should be made that implies 100% protection from UV radiation (such as ‘sunblock’, ‘sunblocker’ or ‘total protection’); (Sect 2, Point 5)

- No claim should be made that implies that there is no need to re-apply the product under any circumstances (such as "all day prevention") (Sect 2, Point 5)

- Claims indicating the efficacy of sunscreen products should be simple, unambiguous and meaningful and based on standardised, reproducible criteria (Sect 4, Point 11)

- Claims indicating UVB and UVA protection should be made only if the protection equals or exceeds the levels set out in point 10 of Section 3 of the Recommendation, i.e. a UVB protection of sun protection factor 6; a UVA protection factor of at least 1/3 of the sun protection factor; a critical wavelength of 370 nm. More on protection factors here (Sect 4, Point 12)

- More under the following content section B

CHANNEL RULES

The cosmetics sector does not attract any sector-specific channel/ placement rules; as with content rules, the channel rules that apply to all sectors should be observed. These are set out in full below under the General tab; brief references follow here. Four principal statutory influences direct traffic in commercial communications in Germany: the State Media Treaty MStV (DE / EN) governs audio-visual media services, some in telemedia, and sets out the rules for broadcast commercial communications. The Telemedia Act (DE 2020; EN key clauses, including those for video-sharing platforms) covers electronic information services in an e-Commerce context under Section 6 and the 2010 Law against Unfair Competition (UWG) implements article 13 of the e-Privacy Directive 2002/58/EC, regulating unsolicited commercial communications in UWG Article 7. The new Federal Data Protection Act (EN) accompanies the introduction of personal data processing rules from the GDPR and implements Directive 2016/680. Finally, Guidelines for labelling advertising in online media (May 2022; EN): this guideline from the State Media Authorities applies to all sectors and is therefore shown under the General tab below, but as it is relatively recent and on a topical issue relevant to the sector, we highlight it here.

General

SECTION A OVERVIEW

Updates since March 2023 (slimmed)

Wettbewerbszentrale and new UWG rules (DE)

Influencer marketing: enforcement time

Reed Smith LLP/ Lex March 6, 2023

Courts disagree on 'climate-neutral' (DE)

Heuking Kühn Lüer Wojtek July 19, 2023

Also on climate neutral Harting/ Lex July 17, 2023 (EN)

Carbon neutrality and environmental neutrality (DE)

Case law report Taylor Wessing August 2, 2023

Sustainability in advertising (DE) CMS Nov 29, 2023

Taylor Wessing again; more from the Karlsruhe court

Generative AI/ GDPR/ EDPS (DE) Noerr June 5

New case law on advertising online reviews (EN)

Reed Smith LLP/ Lex August 7, 2024

Bardehle Pagenberg on the 'climate neutral' case

DLA Piper Environmental Advertising Claims Guide

Above from August 7, 2024 includes Germany

Legal500's Advertising & Marketing Guide

October 11, 2024. Germany chapter linked

Wettbewerbszentrale event calendar 2025 (DE)

Cologne Court on sustainability ads transparency

SKW Schwarz January 13, 2025

Flixbus greenwashing case (FR) March 7, 2025

Above relates to DE Fed court decision

Luifthansa 'greenwashing'. Barron's Mar 24, 2025

Higher regional court on neutrality, ambiguity

SKW Schwarz March 12, 2025 (EN)

DSA News Hub (DE) CMS May 9, 2025

Green Claims Directive news Politico

June 23, 2025. Big wobble as Italy pulls

Simplification Omnibus - EU-Kommission plant

Vereinfachung der CS3D Gleiss Lutz Feb 25, 2025

Federal Court of Justice and 'climate neutral' (DE)

From Sustainable Views EN commentary June 28, 2024

Wettbewerbszentrale, who brought the action, here (DE)

SELF-REGULATION

The German system has two self-regulatory organisations: the German Advertising Standards Council Deutscher Werberat (DW), which deals with issues of social responsibility, taste and decency – codes of conduct here EN / DE; and the Centre for Protection against Unfair Competition Wettbewerbszentrale (WBZ), which is statutorily authorised to initiate legal action against those who infringe or appear to infringe competition laws. Both of these SROs are affiliated to the German Advertising Federation (Zentralverband tier deutschen Werbewirtschaft ZAW), which represents the whole advertising industry. The DW codes apply to all media, and there are some media-specific provisions, including online per this statement in 2011 DE / EN. In the context of these general advertising rules, relevant DW codes include:

General principles on commercial communications (Oct 2007) EN / DE

Code against personal denigration and discrimination (July 2014) EN / DE; and

Advertising with celebrities EN / DE

The Children’s Code (EN), (DE) set out under the children sector on our home page

A helpful general piece from DLA Piper March 2021: Prohibited and controlled advertising in Germany.

Denigration and discrimination

A significant addition in June 2019 to DW regulation, related to and expanding on the code linked above, is in the form of a guidance 'flyer'. Using some (truly terrible) example 'advertising', this addresses issues of racism, discrimination against and denigration of women and men, stereotyping, nudity and sex in advertising, objectification and ’ageism’. The German version, obviously applicable in this context, is here and our (unofficial and non-binding) translation is here.

The ICC

In making rulings, Deutscher Werberat include the ICC’s Advertising and Marketing Communications Code in its set of considerations, the others being applicable law and their own codes of practice. The ICC Code is here in English (2018 code; 2024 code here) and here (2018 code) in German, the latter applicable - as far as we are aware, there is not yet a German translation of the 2024 code. Extracts are in our content section B that follows.

UNFAIR COMPETITION/ COMMERCIAL PRACTICES

The Law Against Unfair Competition Gesetz gegen den unlauteren Wettbewerb (UWG) DE / EN (key sections 5-7 and the annex linked below; translation does not include amends referenced in para below) is the principal law regulating advertising activities, implementing the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD) 2005/29/EC and the Misleading and Comparative Advertising Directive 2006/114/EC. The law applies to all media and to B2B and B2C. Annex I of the UWG lists 31 commercial practices that are regarded as ‘unfair under any circumstances’: the so-called ‘Blacklist’. This is a significant force in German advertising regulation; the Wettbewerbszentrale (WBZ, see above) is statutorily authorised to initiate legal action against infringement of competition laws, a relatively unusual arrangement in European advertising regulation. A March 2021 article from DLA Piper via Lexology, Misleading advertising practices in Germany (EN), sets out the rules. Q&A: online advertising in Germany from SKW Schwarz/ Lex September 24, 2024, as the title suggests, is more specific.

The UWG was amended by the Law to strengthen consumer protection in competition and trade law (DE) of August 17, 2021; this act inter alia transposes Directive 2019/2161/EU, which covers significant commercial territory such as price reductions (see below under Pricing) and the validity of consumer reviews and search rankings but does not hugely impact the content of commercial communications. There are, however, implications for Influencer messaging, for 'invitations to purchase' and for the way in which brands are presented multinationally if product composition differs materially. More here in the form of an explanatory GRS note in English. The law came into force May 28, 2022. The Centre for Protection against Unfair Competition Wettbewerbszentrale (WBZ), referenced above, has brought several actions (DE) against alleged breaches of these new rules, especially those relating to search rankings information.

ENVIRONMENTAL CLAIMS

Germany's regulation of environmental claims is relatively unusual in Europe in as much as it is the statutory versus self-regulatory process that is more regularly deployed.

There's no lengthy environmental code as in the UK and France, for example, but the Wettbewerbszentrale are very active in this territory and the courts similarly and consequently.

Claims are assessed against the UWG (see above)

Green Claims Directive news Politico

June 23, 2025. Big wobble as Italy pulls

Advertising with Carbon Offsetting - The Legal Framework

in Germany Now and to Come Nishimura & Asahi May 16, 2025

WBZ sustainability pages (DE) as at Dec 2024

From above, see BMJ draft EMPCO implementation

Federal Court of Justice and 'climate neutral' (DE)

From Sustainable Views EN commentary June 28, 2024

German case law on the term “climate neutral” (klimaneutral), “environmentally neutral” (umweltneutral)

CMS Germany/ Lex September 5, 2023. A comprehensive review of some definitions and cases

Green Advertising in Germany - making carbon neutral claims. Taylor Wessing/ Lex April 3, 2023

In Germany, competitors and consumer associations may challenge environmental claims as unfair commercial practices, which are therefore assessed against the UWG (see above). As that act is derived from European UCPD legislation, Commission Guidance (December 2021) is obviously relevant: section 4.1.1. Environmental claims. Industry self-regulation is in the form of chapter D of the ICC Code linked earlier and here (EN 2024) and the ICC Framework for Responsible Environmental Marketing Communications (November 2021). See environmental claims in our content section B below for full information. May 19, 2021 WBZ objected to various advertisements in connection with the statement “climate neutral” as misleading and non-transparent; information here (DE). A May 2021 article from CMS Germany/ Lex Sustainability, Advertising and Greenwashing discusses some of the broader claims and their legal compliance and the December 2021 piece Beware of advertising with 'climate-neutral' and 'CO2 reduced' from the same source covers the background to a case that the WBZ brought re climate neutral. This August 2022 Bird&Bird piece Advertising “climate-neutral” production conditions reports on an appeal heard by by the Higher Regional Court of Schleswig, which overturned an earlier judgement that a climate-neutral claim was misleading. And Trend Nachhaltigkeit - Werbung mit Green Claims from Harting November 2022 (EN) rounds up the legal context, references some cases and sets out EU developments. ICLG's Consumer Protection Laws and Regulations from April 2023 explains how various jurisdictions, Germany included, apply consumer protection law to environmental claims.

Internationally, the WFA launched their Planet Pledge in April 2021 and Global Guidance on Environmental Claims April 2022; Green Trademarks vs. Green Claims Directive - Droht „Klimamarken“ die Löschung? (DE) SKW Schwarz july 25, 2024 covers the EU ground, focusing on green trademarks/ certification. DLA Piper's August 2024 Environmental Advertising Claims Guide covers all key markets including Germany.

CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE

The DW publish The Children’s Code (EN), which is set out in full under the children sector on the home page of this website. The Interstate Treaty on the Protection of Minors (Jugendmedienschutz-Staatsvertrag, JMStV; DE, as amended 2020 to incorporate e.g. video-sharing platforms) sets down rules for the providers of both telemedia and broadcasting services; article 6 (EN, as amended 2020) relates largely to commercial communications' content rules for the protection of minors, and is transposed from the AVMS Directive 2010/13/EU and its amending Directive 2018/1808. Also relevant is article 4 DE / EN of the Youth Protection Guidelines (Jugendschutzrichtlinien JuSchRiL) which substantiate/ extend the legal requirements of JMStV. As far as we can establish this has not been amended in light of revisions to the media acts and treaties. A separate ‘children’ category devoted entirely to rules for marcoms aimed at children, per above, is on the home page of this website.

CHANNEL RULES

There's a helpul and comprehensive Media Regulatory Update Series courtesy of Baker McKenzie/Lexology here.

This is largely about, however, consumer protection measures not directly related to marketing communications.

Q&A: online advertising in Germany from SKW Schwarz Rechtsanwälte/ Lex September 2023 is more specific to advertising.

Influencer marketing

Influencer Marketing – legal and practical information (DE)

Wettbewerbszentrale Webinar Mar 18, 2025. Review here (DE)

The labelling of advertising in Influencer marketing (DE) WBZ August 2024

Influencer marketing: enforcement time. Reed Smith LLP/ Lex March 6, 2023

Do German corporate influencers have to label their posts as advertising? SKW Schwarz/ Lex February 20, 2023

A high profile case in April 2019 involved Cathy Hummels, who won an action brought by the Social Advertising Association (VSW) on unlabelled posts is interesting because the court decided that there was no proof she had been paid, albeit they also stated the case was specific to this influencer. In January 2019, Wettbewerbszentrale (WBZ - see above) published updated Guidelines for Influencer Marketing (DE) supplanted, we assume, by The labelling of advertising in Influencer marketing (DE) of August 2024. This is important guidance in this territory and sets out requirements as established largely in case law, ergo:

'Verbung' and 'Anzeige' are the established ad identifier terms where the likes of

#ad, collaboration, sponsored by, (paid) partnership don't cut it

And the terms must be clearly recognisable in the post - 'at first glance'

Helpful blog on recent case law here from the International Trademark Association, and a thorough and valuable review from Hogan Lovells here. A significant development is the May 2022 flyer 'Labelling of advertising in online media' (DE / EN) from the state media authorities; press release here (DE). This distinguishes by medium and separates video and audio (for podcasts). Further significant development is the September 2021 German Federal Court of Justice decision outlined by Hogan Lovells, suggesting a very specific case-by-case approach by the courts. This November 2021 article from the World Trademark Review also via Lex covers similar ground and refers to the UWG amendment referenced above. Finally, ERGA's 2021 Analysis and recommendations concerning the regulation of vloggers (EN), also referenced below. Not quite finally: this Labelling as advertising in social media posts (EN) is an important piece from Hogan Lovells/ Lex July 27, 2022, explaining a judgement of the higher District Court of Frankfurt against an influencer and third party in the context of the amended version of the UWG and, for good measure, the State Media Treaty and the Telemedia Act. Definitely finally: DLA Piper's Influencer Marketing Guide of April 2022, which covers a number of jurisdictions including Germany, is here.

Audiovisual media

The State Media Treaty (MStV; DE / EN), in force November 2020 and replacing the Interstate Treaty on Broadcasting (RStV), carries the provisions of the AVMS Directive 2010/13/EU and its amending Directive 2018/1808. The treaty sets out the rules for commercial communications - including teleshopping, sponsorship and product placement - in the expanded scope, which now incorporates e.g. online audio and video libraries, search engines, streaming providers and social networks. Rules are set out in the following sections B and C; the relevant Directive content amends for commercial communications are shown here and are not especially significant, though there are implications for Food advertising self-regulation in particular (see home page of this website for that sector). This development reflects the digitisation of European media regulation and has most impact on platforms (versus advertisers), in terms of child protection, search results management etc. There's a helpful blog explaining the structures from DLA Piper here and ERGA's 2021 Analysis and recommendations concerning the regulation of vloggers is the definitive regulators' view on whether vlogging is in scope. The Telemedia act referenced below also receives some of the directive's amends.

Online privacy and information

Das Ende der Cookie-Banner? (DE) CMS May 19, 2025

Consent Management Ordinance (EN) Heuking Sept 24, 2024

Changes To The BDSG And TTDSG (EN) Heuking June 27, 2024

EDPB data protection guide for small businesses in FR & DE

EDPB May 17, 2024

Privacy Sandbox news and updates

In May 2021, the Bundestag approved the Telecommunications-Telemedia Data Protection Act (TTDSG; DE). The privacy provisions from the Telecommunications Act and the Telemedia Act are merged in this new main law, which will be in line with GDPR and the e-Privacy Directive 2002/58/EC, for a long time supposedly 'covered' in Germany by the Telemedia Act. See section 25 for specifics on cookies; the TTDSG entered into force December 1, 2021. Legal regulation for the use of cookies (EN) from SKW Schwarz Rechtsanwälte/ Lexology October 2021 is helpful explanation as is a Stripe commentary (EN) November 2023. From Covington January 2022: on 22 December 2021, DSK (see below) published its Guidance for Providers of Telemedia Services (Orientierungshilfe für Anbieter von Telemedien). Particularly relevant for providers of websites and mobile applications, the guidance is largely devoted to the 'cookie provision' of the TTDSG. The publication focuses on the consent requirement for cookies and similar technologies, as well as relevant exceptions, introduced by the law; full article with extracts of the DSK guidance in English here and the guidance itself here (DE). New guidance November 2024 here (DE); see our Cookies and OBA header for more.

The Telemedia Act, which was the home of marcoms-related clauses from the e-Commerce Directive, was repealed on May 14, 2024, when the Digital Services Act/ Digitale-Dienste-Gesetz (DDG) came into force; DE version here. E-Commerce clauses are now found under Section 6 of the DDG, which is the recognition of the EU's Regulation of the same name. DDG lays the foundation for enforcing the EU Digital Services Act in Germany (EN), same date as the act came into force, is helpful explanation from Taylor Wessing.

The Telemedia Act TMG DE / EN under section 6 delivers the marcoms-related clauses from the e-Commerce Directive 2000/31/EC. The TTDSG makes some amends to the TMG under article 3, though the TMG section 6 provisions that set out e-Commerce information requirements remain under what will become, when the TTDSG comes into force, section 5. Still with us? Additionally, the TMG was amended in November 2020 (DE) to absorb the scope changes to the AVMSD brought about by Directive 2018/1808, which now includes in its remit e.g. video-sharing platforms.

GDPR

Privacy issues should be reviewed with specialist advisors

Changes To The BDSG And TTDSG. Heuking June 27, 2024

The General Data Protection Regulation 2016/679 (GDPR) applied directly in all EU member states from 25 May 2018, replacing the Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC. The European Commission page on GDPR is here. A table here sets out how GDPR relates to some marketing techniques and channels, and to other legislation that applies in marketing, though it is a somewhat broad and selective picture and subject to national differences in application. Member states, Germany included, tend to retain their national privacy legislation and add to it to ‘recognise’ and flank GDPR. Germany’s key data protection law, duly amended, is the Federal Data Protection Act (BDSG - EN). The German Data Protection Authority BfDI, which publishes some text in English, is the best national source for data protection issues, together with the Data Protection Conference (DSK – Datenschutzkonferenz). On a European level, some guidelines related to GDPR are in our links section E; example is April 2021 European Data Protection Board guidelines on the targeting of social media users here. Specific rules related to all of the above four paras are set out by channel in our following section C.

FREEDOM OF ADVERTISING SPEECH

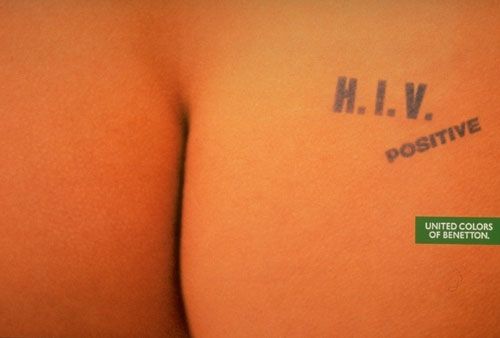

Germany’s ‘Basic Law’ (Grundgesetz GG) is the constitution of the Federal Republic; case law (Benetton) establishes that the fundamental right to freedom of expression in article 5 applies to advertising EN / DE; see also the ‘shock advertising’ sub-head in our following content section B.

PRICING

From the Price Indication Ordinance (PAngV) DE (see below for amended version). When a price is included in consumer advertising, the information obligations in the ordinance must be observed; in particular, the total price inclusive of VAT and other price components must be specified (s.1 (1)). See the pricing section in content section B for full information. Pricing in advertising is often a source of complaint, both consumer and competitor, and sometimes competitor litigation. It’s best to check prices in ads, especially new ads, with legal advisors.

Directive 2019/2161/EU amends the Product Pricing Directive (PPD) 98/6/EC to introduce rules related to promotional pricing, extracted from the Directive here and transposed in Germany by the Ordinance amending the Price Indication Ordinance of November 2021 (Verordnung zur Novellierung der Preisangabenverordnung) DE, under section 3/11, which came into force May 28, 2022. Helpful December 2021 piece on the issue from CMS Germany here. Commission guidance on the application of the article in question (6a of the PPD) here and ECJ '30 day' judgement Aldi promotional pricing September 24, 2024 case is here; Pinsent Oct 4 commentary here.

International

SECTION A OVERVIEW

|

DLA Piper Global Influencer guide Coke's aspirational claims are not actionable FKK&S/ Lex November 20, 2022 Meta’s Ad Practices Ruled Illegal Under E.U. Law. Jan Proposal for a Directive on Green Claims Cheat sheet EU Digital Acts April 23, 2023 Green Initiatives mainly in Europe April 2023 Our assembly of some key EU 'green' requirements A brief guide to EU institutions. April 25, 2023 Self-regulation globally. FKK&S April 27, 2023 EASA Influencer Disclosure pan-Europe July 2023 EU Influencer Legal Hub. Posted October 2023 Council Influencer conclusions May 14, 2024 |

Emerging Advertising Law Issues in Asia Pacific GALA September 24, 2024 (Aus, India, Japan, NZ) Quarterly report from Global Advocate Nov 22, 2024 Markets UK, France, Neths, China, EU Advertising, marketing international quarterly* (EN) Countries China, EU, France, Hong Kong, Italy, Netherlands, UK ECJ re price information GALA April 15, 2025 IMCO newsletter Apr 11, 2025 Key issues DMA, NLF, eCommerce product safety, toy safety, green claims, AI code EASA Policy Newsletter April 2025. Issues AVMSD, DFA (Digital Fairness Act), AI regulation, Health, Children protection and BIK EASA Policy Newsletter May 2025 Issues AVMSD, Influencers, AI transparency, Minors protection, consumer protection inc green claims and DFA, internal market EASA Policy Newsletter June 2025 Issues Minors, age verification, AI act, Green Claims Directive, ISO digital marketing standard, political advertising EC, Shein dark practices. Slaughter May 12/6/25 |

* Recommended read

Advertising, Media and Brands - Global HotTopics

Squire Patton Boggs June 30, 2025 Jurisdictions Asia-Pacific, EU, UK, USA

Fears EU caves to US on tech rules

Politico June 23, 2025

Green Claims Directive news Politico

June 23, 2025. Big wobble as Italy pulls

Omnibus - CSRD/CSDDD developments

Hogan Lovells May 28, 2025

AI

EC Guidelines on Prohibited AI Practices

Part I. CMS Feb 7, 2025. Guidelines here

The AI Convention CSC Sept 12, 2024 here

AI Global Regulatory Update. Eversheds Sutherland Feb 22, 2024

EU AI Act: first regulation on artificial intelligence. June 2023

Visual summary of the EU's AI Act's risk levels here

Green Claims Directive news Politico

June 23, 2025. Bird&Bird on the above 26th

Anti-greenwashing in the UK, EU and the US:

the outlook for 2025 and best practice guidance

Charles Russell Speechlys June 9, 2025

Greenwashing: An International Regulatory Overview

KPMG. 25 jurisdictions. Copyright 2024

There's an almost constant barrage of new and developing rules and regulations all around the world on this issue and especially in Europe, which is where we start. We think it's helpful first to distinguish between 'consumer' rules i.e. those that apply to business-to-consumer communications, and 'corporate' rules, which are those that apply to corporate 'ESG' reporting and financial services sector to investors, though the former ad rules will also apply to the financial sector when they advertise (the corporate reporting and due diligence rules don't per se apply in advertising, but we include them later so as to complete 'the green picture'). Anyway, consumer rules first as that's where most of our interests lie. In Europe, you need to be aware in particular of two directives driving the commercial communications elements of the 'Green deal' agenda:

1. The 'Empco' Directive 2024/825, full title and directive here, which was in force from March 2024, meaning that member states have until September 2026 to implement. Basically, and for our purposes, the Directive is an amendment of the seminal UCPD 2005/29/EC which forms the cornerstone of consumer protection rules in Europe. New environmentally-specific clauses are added to the 'blacklist' and e.g self-certification is banned. There's a good summary here from Taylor Wessing. Clauses are placed in our following content section B.

2. The Green Claims Directive. The Commission pages on the proposed new law, which has new requirements for substantiation and verification of green claims, are here. The European Parliament is expected to reach final agreement before the end of 2024 update here Dec 10, 2024 from IMCO Internal Market and Consumer protection European Parliamentary Committee; there's likely to be an extended implementation period. A good June 2024 summary here from Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer and EASA's update from December 2024 here

Navigating the Future of Green Claims in the EU. GALA March 25, 2025 (webinar)

Greenwatch: Issue 6 Ashurst EU and UK March 12, 2025 Issues Omnibus, ESMA guidelines, UK Principles for voluntary carbon and nature market integrity, WPP

Navigating the increasing scrutiny of green claims

Slaughter and May November 19, 2024. EU, UK. Audio

Standards for Claims of “Carbon Neutral” and “Climate Friendly”

Formosan Bros Oct 4, 2024. Countries Australia, European Union, OECD, Taiwan, UK

See Omnibus announcements above

A Practical Guide to Greenwashing for Financial Institutions

Baker McKenzie March 25, 2025. International

Update Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive Transposition

Ropes & Gray December 20, 2024

CSDDD FAQs Proskauer October 4, 2024

FAQs on the implementation of the EU corporate sustainability reporting rules

From the Commission August 7, 2024. Ropes & Gray unpack them here

ESMA Guidelines on funds’ names using ESG/ sustainability terms. Aug 2024

As this aspect of the green deal is not directly ad-related and as there's so much ground to cover, we've linked the information here

This analysis of the four key directives from White & Case July 8, 2024 is helpful in explaining their roles and see also Regulation Across Jurisdictions from Sidley Austin July 17, 2024

National rules applicable to influencers

European audiovisual observatory. Posted May 2025

Influencer Marketing Practices Under Scrutiny In Europe

Greenberg Traurig April 15, 2025

Understanding consumer law when conducting influencer marketing

campaigns in the EU and UK. BCLP October 7, 2024

This is a high profile and somewhat controversial (in regulatory terms) marketing technique that’s deployed right across the world. Most jurisdictions, in Europe at any rate, publish specific rules or guidelines, be they from statutory consumer protection authorities increasingly involved or, more frequently, self-regulatory organisations. The big and consistent issue is obviously identification when a post is an ad, when it's been incentivised in some way; less consistent is the way that authorities require that identification to be made, so check the rules/ guidelines in each country. A number including the US and Canada, Belgium, France, Italy, The Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Australia and China have been assembled by the admirable DLA Piper in their Global Influencer Guide published 2022. For other international rules/ guidelines see ICPEN's Guidelines for Digital Influencers, which dates back to 2016 and the IAB's 2018 Content & Native Disclosure Good Practice Guidelines. August 7, 2024 GALA discuss ARPP's (French self-reg organisation) Certificate of Responsible Influence here and EASA's (the European self-regulatory network) expansion of that is set out here.

The European Commission got interested some time ago and has issued various edicts/ hubs/ guidelines, as is its wont:

The Commission publish The Influencer Legal hub 'These resources are for anyone making money through creating social media content.' and 'The information in the Influencer Legal Hub reflects the position of the Consumer Protection Cooperation Network which adopted the 5 Key Principles on Social Media Marketing Disclosures.' On May 14, 2024, the EU Council approved ‘Conclusions on ways to support influencers as online content creators in the EU.’ Bird&Bird on that here June 12.

In the US, the key rule maker is the FTC (Federal Trade Commission, a government agency), which issues a number of guidelines, the most important of which are:

Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising

Disclosures 101 for Social Media Influencers

FTC Requirements For Influencers: Guidelines and Rules

Termly Feb 2, 2024 published FTC Requirements For Influencers: Guidelines and Rules, a good summary by platform

In self-regulation, the National Advertising Division (NAD) of the Better Business Bureau (BBB) make available a number of cases here; the BBB's ad code is here, clause 30 Testimonials and Endorsements. The key issue, defined by FTC and deployed by NAD, is any 'material connection' between advertiser and influencer and the adequacy of its disclosure, which must be 'clear and conspicuous.' See the US 'general rules' database on this website for more.

ASCI's June 2021 Guidelines for Influencer advertising in digital media (link to a downloadable pdf). Additionally, from the CCPA's Guidelines for Prevention of Misleading Advertisements and Endorsements 2022 (CCPA guidelines): 14. Disclosure of material connection (the same term used by ASCI). 'Where there exists a connection between the endorser and the trader, manufacturer or advertiser of the endorsed product that might materially affect the value or credibility of the endorsement and the connection is not reasonably expected by the audience, such connection shall be fully disclosed in making the endorsement.' In January 2023 the Department of Consumer Affairs, who administer the Consumer Protection Act, issued 'Endorsement know-hows' on when and how to disclose a 'material relationship.' Commentary from SS Rana/ Lex here. Additional Influencer Guidelines for Health and Wellness Celebrities, Influencers and Virtual Influencers August 10, 2023 by the Consumer Protection Authority (CCPA) is here. Summary of Influencer rules from Kan & Krishme/ GALA December 7, 2023 is here.

1.1 The ICC Code

The latest ICC Code was published September 18, 2024

French trans Nov 7, 2024. SW here, ES here

The code is structured in two main sections: General Provisions and Chapters. General Provisions sets out fundamental principles and other broad concepts that apply to all marketing in all media. Code chapters apply to specific marketing areas, including Sales Promotions (A) Sponsorship (B) Direct Marketing & Digital Marketing Communications (C) Environmental Claims in Marketing Communications (D) and a new chapter Teens and Children (E). The Code 'should also be read in conjunction with other current ICC codes, principles and framework interpretations in the area of marketing and advertising':

ICC Guide for Responsible Mobile Marketing Communications

Mobile supplement to the ICC Resource Guide for Self-Regulation of Interest Based Advertising

ICC Framework for Responsible Marketing Communications of Alcohol

ICC Resource Guide for Self-Regulation of Online Behavioural Advertising

ICC Framework for Responsible Environmental Marketing Communications (2021)

ICC Framework for Responsible Food and Beverage Marketing Communication

Key rules are set out in the following content section B and channel section C, as applicable

- The new (Sept 2024) code adds a whole new chapter E on Children and Teens as well as articles 20 and 22 under General Provisions and articles C5 and 17.8 under Chapter C, Data-driven Marketing, Direct Marketing, and Digital Marketing Communications

- Also worthy of note is the International Consumer Protection Enforcement Network (ICPEN), a network of consumer protection agencies from over 60 countries, who publish Best Practice Principles for Marketing Practices Directed Towards Children Online (June 2020)

- On the home page of this website, you'll find a complete children's sector with the rules spelt out country by country

Lawyer commentary

Kids and Teens Online Safety and Privacy Roundtable

Baker Mckenzie July 26, 2023. Canada UK and USA. Video

EU: Two Key Decisions Highlight Issues When Handling Children's Data

Collyer Bristow/Lex 21 June, 2023

The rules are both 'horizontal', i.e. they apply across product sectors, and the ICC also publish 'vertical' sector-specific framework rules such as those for Alcohol, or Food and Beverages (as linked above). While these rules are referenced in the sections that follow, we don't extract them in full as these product sectors are covered by specific databases on this website. These sector rules in particular need to be read with a) the general rules that apply to all product sectors and b) the specific legislation and self-regulation that frequently surrounds regulation-sensitive sectors. Channel rules from the ICC Code, such as those for OBA, are shown within the relevant sub-heads under our channel section C, together with the applicable European legislation.

European Regulations and Directives

| Issue or channel | Key European legislation and clauses |

| Cookies |

The EU ‘Cookies Directive’ 2009/136/EC

articles 5 and 7, which amended the E-Privacy Directive 2002/58/EC

|

| Electronic coms. Consent and Information |

Articles 5 (3) and 13

|

|

E-commerce; related electronic communications

|

Directive on electronic commerce 2000/31/EC of 8 June 2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/31/oj

Articles 5 and 6

|

| Marketing Communications |

Directive 2005/29/EC on unfair business-to-consumer commercial practices

Articles 6, 7, 14 (amendments re comparative advertising), Annex I

December 2021 Commission guidance. See Omnibus Directive below; also amended by the Empco Directive see Environmental Claims section

|

| Audiovisual media |

Directive 2010/13/EU concerning the provision of audiovisual media services (Audiovisual Media Services Directive; consolidated version) Directive 2018/1808 extended some rules into especially video-sharing platforms |

| Data Processing |

Regulation 2016/679/EU on the processing of personal data (GDPR) |

Two relatively recent arrivals in EU digital platform regulation are the Digital Markets Act (implemented May 2023), aka Regulation (EU) 2022/1925 and its implementing provisions; Commission explanatory pages here and the Digital Services Act, pages here (implemented Feb 2024 for all platforms) aka Regulation 2022 (EU) 2022/2065. The first, as the name implies, is the EU's means of reining in the major digital 'gatekeepers' to ensure 'fairer and more contestable' markets. Somewhat obviously, the rules are aimed at platforms rather than advertisers and agencies, though there are implications for behaviourally targeted advertising. The DSA's main goal 'is to prevent illegal and harmful activities online and the spread of disinformation.' Loosely, this is the EU's Online Safety Act. On February 13th 2025, the Commission endorsed the integration of the voluntary Code of Practice on Disinformation into the framework of the DSA. PR here (EN), with implications for political advertising.

EACA and EDAA and AATP and DSA

From EACA newsletter June 2025

DSA decoded #4: Advertising under the DSA

Freshfields May 14, 2025

Shaping The Future Of Tech: Latest Updates On The Digital Markets Act

Quinn Emanuel/ Lex October 10, 2024

Rules for data processing, consent and information in digital communications in Europe are shown above under the Directives table and in our channel section

See the US general rules on this database for privacy/ processing rules in that jurisdiction. Below are some key legal commentaries on this topic

Two-min Recap of Data Protection Law Matters Around the Globe

April 4 2025 Gen Temizer. Some high profile cases

EMEA- Data Privacy, Digital and AI Round Up 2024/2025

BCLP January 14, 2025. Countries Canada, European Union, France, United Kingdom, USA

Data Privacy Insights To Take into 2025. BakerHostetler Dec 19, 2024

Countries: Australia, Canada, European Union, United Kingdom, USA

Meta to offer less personalized ads in Europe. Reuters Nov 12, 2024

Data Protection & Privacy: EU overview. Hunton Andrews Kurth July 3, 2024*

EDPB Opinion 8/2024 on Pay or Consent April 17. Lexia May 8

Report from the Commission to the European parliament and the Council on implementation

June 18, 2024. Commentary from Lewis Silikin July 9, 2024 here (See third entry)

Directive 2019/2161, known as the Omnibus Directive sets out new information requirements for search rankings and consumer reviews, new pricing information in the context of automated decision-making and profiling of consumer behaviour, and price reduction information under the Product Pricing Directive 98/6/EC. More directly related to this database, and potentially significant for multinational advertisers, is the clause that amends article 6 (misleading actions) of the UCPD adding ‘(c) any marketing of a good, in one Member State, as being identical to a good marketed in other Member States, while that good has significantly different composition or characteristics, unless justified by legitimate and objective factors’. Recitals related to this clause, which provide some context, are here. Helpful October 2021 explanatory piece on the Omnibus Directive from A&L Goodbody via Lex here. Provisions were supposed to have been transposed and in force in member states by May 28, 2022, though there were several delays, now resolved.

...............................................................

Sections B and C below set out the rules that are relevant to marketing communications from the directives above, together with the self-regulatory measures referenced under point 1 in this overview.

Reference work versus current available in back-up here. More recent below:

ICAS 2024 Global Factbook of SROs March 2025

GALA Year in Review Dec 10, 2024 Countries Canada, South Africa, Slovakia, Mexico, Turkey, India

Advertising, Media and Brands Global Hot Topics Squire Patton Boggs Sept 16, 2024

Legal500's Advertising & Marketing Guide - An International Perspective

October 2024. Incs UK , China, India, Japan, Mexico, Peru, Denmark, Germany, Canada

B. Content Rules

Sector

SECTION B CONTENT RULES

THE CPR 1223/2009 AND CLAIMS REGULATION 655/2013

1.1. The CPR

1.2. The Claims Regulation Common Criteria and guidelines

1.3. Guidelines for ‘free from' claims

1.4. Guidelines for ‘hypoallergenic’ claims

1.5. Other claims – ‘natural’ and ‘organic’

1.7. Animal testing (absence of)

2.1. Section 27 LFGB

2.2. Extracts from WBZ Reviews showing case law

- COSMETICS EUROPE

- GENERAL RULES with particular relevance to cosmetics

4.1. DW 'Ground rules’

4.2. DW Denigration and discrimination

4.3. ICC Code and framework

4.4. UCPD Guidance on environmental claims

4.5. Legislation in marketing communications in Germany

1. THE CPR 1223/2009 AND CLAIMS REGULATION 655/2013

1.1. The CPR 1223/2009

- The CPR carries one key article specific to claims in marketing communications - Article 20. From that: 1. ‘In the labelling, making available on the market and advertising of cosmetic products, text, names, trade marks, pictures and figurative or other signs shall not be used to imply that these products have characteristics or functions which they do not have.’

- 3. The responsible person may refer, on the product packaging or in any document, notice, label, ring or collar accompanying or referring to the cosmetic product, to the fact that no animal tests have been carried out only if the manufacturer and his suppliers have not carried out or commissioned any animal tests on the finished cosmetic product, or its prototype, or any of the ingredients contained in it, or used any ingredients that have been tested on animals by others for the purpose of developing new cosmetic products

- The article also requires: ‘the Commission shall adopt a list of common criteria for claims which may be used in respect of cosmetic products, in accordance with the regulatory procedure with scrutiny referred to in Article 32 (3) of this Regulation, taking into account the provisions of Directive 2005/29/EC.’ (Note: that’s the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive which we cover later and below under the General tab. All that’s being said here is that the nature of the common criteria should be consistent with ‘horizontal’ provisions in the UCPD)

1.2. The Claims Regulation 655/2013

The acceptability of a claim made on a cosmetic product is determined by its compliance with the 'Common Criteria'. The 2017 (non-binding) Technical document on cosmetic claims is 'a collection of best practice for the case-by-case application of union legislation by the member-states.' Guidelines/ best practice for each of the criteria below are shown in Annex I of the technical document

1. Legal compliance

- Claims that indicate that the product has been authorised or approved by a competent authority within the Union shall not be allowed

- The acceptability of a claim shall be based on the perception of the average end user of a cosmetic product, who is reasonably well-informed and reasonably observant and circumspect, taking into account social, cultural and linguistic factors in the market in question

- Claims which convey the idea that a product has a specific benefit when this benefit is mere compliance with minimum legal requirements shall not be allowed

2. Truthfulness

- If it is claimed on the product that it contains a specific ingredient, the ingredient shall be deliberately present

- Ingredient claims referring to the properties of a specific ingredient shall not imply that the finished product has the same properties when it does not

- Marketing communications shall not imply that expressions of opinions are verified claims unless the opinion reflects verifiable evidence

3. Evidential support

- Claims for cosmetic products, whether explicit or implicit, shall be supported by adequate and verifiable evidence regardless of the types of evidential support used to substantiate them, including where appropriate expert assessments

- Evidence for claim substantiation shall take into account state of the art practices

- Where studies are being used as evidence, they shall be relevant to the product and to the benefit claimed, shall follow well-designed, well-conducted methodologies (valid, reliable and reproducible) and shall respect ethical considerations

- The level of evidence or substantiation shall be consistent with the type of claim being made, in particular for claims where lack of efficacy may cause a safety problem

- Statements of clear exaggeration which are not to be taken literally by the average end user (hyperbole) or statements of an abstract nature shall not require substantiation

- A claim extrapolating (explicitly or implicitly) ingredient properties to the finished product shall be supported by adequate and verifiable evidence, such as by demonstrating the presence of the ingredient at an effective concentration

- Assessment of the acceptability of a claim shall be based on the weight of evidence of all studies, data and information available depending on the nature of the claim and the prevailing general knowledge the end users

4. Honesty

- Presentations of a product’s performance shall not go beyond the available supporting evidence

- Claims shall not attribute to the product concerned specific (i.e. unique) characteristics if similar products possess the same characteristics

- If the action of a product is linked to specific conditions, such as use in association with other products, this shall be clearly stated

5. Fairness

- Claims for cosmetic products shall be objective and shall not denigrate the competitors, nor shall they denigrate ingredients legally used

- Claims for cosmetic products shall not create confusion with the product of a competitor

6. Informed decision-making

- Claims shall be clear and understandable to the average end user

- Claims are an integral part of products and shall contain information allowing the average end user to make an informed choice

- Marketing communications shall take into account the capacity of the target audience (population of relevant Member States or segments of the population, e.g. end users of different age and gender) to comprehend the communication. Marketing communications shall be clear, precise, relevant and understandable by the target audience

1.3. Guidelines for ‘free-from' claims

- From the Technical document on cosmetic claims (EN) agreed by the Sub-Working Group on Claims, version of 3 July 2017, also referenced above. We have assembled the specific 'free-from' guidance related to common criteria in a table here

- “In the case of ‘free-from’ claims, more guidance is needed for the application of the common criteria to provide an adequate and sufficient protection of consumers and professionals from misleading claims.”

1.4. Guidelines for hypoallergenic claims

28.02.2022. Wettbewerbszentrale has the meaning of the term “hypoallergenic” clarified (DW)

From Annex IV of the EC's Technical document on cosmetic claims (version of 3 July 2017, per above)

The claim "hypoallergenic" can only be used in cases, where the cosmetic product has been designed to minimize its allergenic potential. The responsible person should have evidence to support the claim by verifying and confirming a very low allergenic potential of the product through scientifically robust and statistically reliable data (for example reviewing postmarketing surveillance data, etc.). This assessment should be updated continuously in light of new data.

If a cosmetic product claims to be hypoallergenic, the presence of known allergens or allergen precursors should be totally avoided, in particular of substances or mixtures:

- Identified as sensitizers by the SCCS or former committees assessing the safety of cosmetic ingredients

- Identified as skin sensitizers by other official risk assessment committees

- Falling under the classification of skin sensitizers of category 1, sub-category 1A or sub-category 1B, on the basis of new criteria set by the CLP Regulation18

- Identified by the company on the basis of the assessment of consumer complaints

- Generally recognized as sensitizers in scientific literature

- For which relevant data on their sensitizing potential are missing

- The use of the claim "hypoallergenic" does not guarantee a complete absence of risk of an allergic reaction and the product should not give the impression that it does.

- Regarding the use of human data in risk assessment of skin sensitisation, including ethical aspects, reference should be made to the SCCS “Memorandum on use of Human Data in risk assessment of skin sensitisation”, SCCS/1567/15, 15 December 2015.

- The companies should consider whether consumers, in the respective country, understand the claim "hypoallergenic". If necessary, further information or clarification regarding its meaning should be made available; see above under the header for this section for some clarification

1.5. Other claims: ‘natural’ and ‘organic’

- As it stands, the terms ‘natural’ and ‘organic’ are not specifically regulated under Cosmetics rules, although Article 20 CPR and the Common Criteria still apply as they do to all types of cosmetic product claims, whether natural/ organic or otherwise; the claim must not mislead and must be capable of substantiation. Horizontal legislation will also apply, per UCPD 2005/29/EC as transposed into German law in the form of the UWG; see 4.6 below

- Non-mandatory source (soft law): Natural cosmetics guidelines approved by the Council of Europe expert committee on Cosmetics, which provides conditions of use of ‘natural’ claims. Despite dating back to September 2000, the guidelines continue to have some relevance in the absence of specific replacements in European law

- That absence is part explained here: Clarification of the absence of European harmonised standard for natural and organic cosmetics from the DG Sanco (EC Health and Consumer Protection Department) pages 16/10/2015. The bottom line of that explanation is that an International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standard for natural and organic cosmetics was in the process of development. That process has now completed andpublished, but findings/ conclusions do not include claims related to the terms ‘natural’ and ‘organic’

- Cosmetics Claims: When can you claim Natural, Organic, Vegan and Non-GMO? from the Obelis Group March 2022 is helpful: from that: It is essential to highlight that there is no official regulation nor harmonized criteria on the definitions of ‘natural’, ‘organic’, and ‘vegan’. Therefore, while cosmetic product claims have to comply with the above legislation (regulations 1223/2009 & 655/2013), there is no precise interpretation of how these claims apply to products without being considered misleading. ISO 16128-2, to which this piece refers, is here

There are two ‘private’ (non profit) associations who provide standards: Cosmos-Standard, and NaTrue. Further background to those organisations and their publications, and more on all of the above, has been assembled here

Definition: Any preparation (such as creams, oils, gels, sprays) intended to be placed in contact with the human skin with a view exclusively or mainly to protecting it from UV radiation by absorbing, scattering or reflecting radiation (Sect. 1 (2a) CR). The Recommendation applies to 'primary' sun protection products such as beach, mountain or sports products. Daily protection products, such as moisturizers, with labelling of UV protection (even an SPF and/or UVA protection level) will not come under the scope of the Recommendation, as long as they do not claim 'sun protection.' (per Cosmetic Europe Q&A)

The EC pages on sunscreen products documentation and legislation are here. From those:

Sunscreen products are cosmetics according to Regulation 1223/2009. The efficacy of sunscreen products, and the basis on which this efficacy is claimed are important public health issues. In particular:

- Products should contain protection against all dangerous UV radiation

- An indication of the efficacy of sunscreen products should be simple, unambiguous, and meaningful; and it should be based on standardised, reproducible criteria

- Labels and claims should provide sufficient information to help consumers choose the appropriate product and apply it correctly

The EC's Recommendation on the efficacy of sunscreen products and the claims made relating to them, adopted in 2006, addresses these issues and sets out the:

- Claims which should not be made in relation to sunscreen products

- Precautions to be observed including application instructions

- Minimum efficacy standard for sunscreen products in order to ensure a high level of protection of public health

- Simple and understandable labelling to assist in choosing the appropriate product

Prohibited claims: no claim should be made that implies the following characteristics (point 5):

- 100% protection from UV radiation (such as ‘sunblock’, ‘sunblocker’ or ‘total protection’)

- No need to re-apply the product under any circumstances (such as ‘all day prevention’)

Efficacy claims

- Claims indicating the efficacy of sunscreen products should be simple, unambiguous and meaningful and based on standardised, reproducible criteria (point 11)

- Such claims need to be verified by the respective testing methods as outlined in Point 10 and subsequently standardised by ISO and published by European Standardisation Organisation (CEN)

- Claims indicating UVB (Burn) and UVA (Aging) protection should be made only if the protection equals or exceeds the levels set out in Point 10, which provides for the minimum degrees of protection:

- For UVB Protection Claims: SPF Sun Protection Factor rating must be at least 6

- For UVA Protection Claims (including Broad Spectrum claims): a UVA protection factor should be at least 1/3 of the labelled SPF; second criterion a critical wavelength of 370 nm, as obtained in application of the critical wavelength testing method

‘Water-resistant’ claims for sunscreen products

- Claims such as ‘water-resistant’ or ‘very water resistant’ can be made for sunscreen products provided they can be substantiated and comply with common criteria

- Cosmetics Europe publishes Guidelines for Evaluating Sun Product Water Resistance, 2005. 'The method outlined is widely accepted and used by manufacturers to qualify their products and includes substantiation requirements and efficacy levels required for ‘Water Resistant’ (4.5) and ‘Very Water-Resistant’ claims' (4.6)

- If that's a little dusty, Use of appropriate validated methods for evaluating sun product protection of May 2016 states that the above continues to apply in this context and that: 'There is currently no in-vitro method that is proven to give reliable and meaningful test results for water resistance, therefore no in vitro method should be used for consumer information purposes.'

- Claims such as ‘water-proof’ or ‘sweat-proof’ should not be used, as no product is 100% resistant to being washed off with water; it would not be possible to substantiate the claim. Commission recommendation 2006/647/EC does not address this issue directly or ban the use of such claims

- The Commission Recommendation addresses the issue indirectly through labelling instructions such as: 'Re-apply frequently to maintain protection, especially after perspiring, swimming or towelling’ (Point 7)

Cosmetics Europe Related guidelines and recommendations

- Recommendation No. 23 Important Usage and Labelling Instructions For Sun Protection Products (2009, updated 2016)

- Recommendation No. 25 Use of Appropriate Validated Methods for Evaluating Sun Product Protection (2013, updated 2016)

1.7. Animal testing (absence of)

Article 20 (3) of the CPR and the accompanying Guidelines (Commission Recommendation 2006/406/EC) allows restricted use of claims in relation to the absence of animal testing, relating to the development or safety evaluation of the product or its ingredients, although it has been argued (by Cosmetics Europe) that such a claim is now obsolete as it would not be in compliance with the common criterion of Legal Compliance (the claimed benefits for a product must go beyond mere compliance with legal requirements). As animal testing is prohibited (testing ban since 11/09/2004 and marketing ban since 11/03/2009), such a claim would be describing a legal requirement

2. NATIONAL LEGISLATION: COSMETICS

The German Food and Feed Code (EN) LFGB (DE) regulates cosmetic products nationally under sections 26 and 27, the latter providing that product claims, information or designs/ presentation must not be misleading:

2.1. Section 27. Regulations on protection against deception

(1) The introduction of cosmetic products onto the market with a misleading name/ description, information/ specification or presentation, or advertising cosmetic products generally or in specific cases with misleading representations or other statements is prohibited. Deception is deemed to exist, in particular, if

- Effects are attributed to a cosmetic product which it does not possess or which have not been adequately verified in scientific terms

- The impression is made incorrectly through the name, description, presentation or any other statement/ claim that success is a guaranteed certainty

- Names, descriptions, presentations, details or any statements likely to mislead or deceive are used with regard to

- The person, educational background, qualification or successes of the manufacturer, inventor or people working for them

- Properties, particularly regarding the nature, quality, composition, quantity, durability, origin or type of production

2.2. Extracts from WBZ reviews showing case law

From WBZ News 09.03.2016 / Cosmetic advertising – Federal Court of Justice:

- Although it must be possible to substantiate advertising claims relating to cosmetic products on the basis of adequate and verifiable evidence, they do not necessarily have to be regarded as being scientifically validated/ proven. This emerges from a ruling recently handed down by the Federal Court of Justice (BGH) (judgement dated 28.01.2016, ref. I ZR 36/141 – Moisturising/ hydrating gel reservoir). In its ruling, the court gave a detailed opinion concerning the requirements to be imposed regarding the verifiability of effect claims for cosmetic products. Full information here

Extracts from the WBZ Annual Report 2014:

- In the last annual report, the Wettbewerbszentrale reported on a company that advertised in a magazine with the statement “95% of testers would recommend the perfume E. to their girlfriends“. The case concerned volume 07/13 of the magazine Glamour. Apart from the fact that the test results were not shared, it turned out in the course of proceedings that the content of the statement was inaccurate. This is because the question “Would you recommend E. to a girlfriend?“ was answered by 66% with “Yes, definitely“, whereas 29% answered with “Yes, probably“. The advertising claim did not reflect this result. Even before a hearing, the other party acknowledged the claim of the Wettbewerbszentrale, so that it ended with a judgment based on acknowledgement (LG Mainz, judgment of 25 April 2014, 10 HK O 1/14; F 4 0847/13).

- Except in the cases of the test or survey advertising, the main focus of the complaints was in the area of misleading statements. A typical example is the advertising of a company that promoted its shampoo in a two-page advertisement with the statement “Moisture & up to 95% more volume“. The asterisk after the word “volume“ was explained on the second page, opposite to the reading direction and barely perceptible, as “vs. unwashed hair“. It is clear that such a comparison is misleading because the consumer does not expect a comparison between washed and unwashed hair (F 4 0490/14)

- Other annual reviews have not yet been translated; links In English: 2014, 2015. In German: 2016, 2017, 2018

- WBZ also provides an overview of the advertising of cosmetic products here (EN) and updates of important cases are also included on the WBZ website; a collection of cases here (EN) has some significant findings on e.g. substantiation of claims

Charter and Guiding Principles on Responsible Advertising and Marketing Communication (2020 version)

Cosmetics Europe is a particularly active and respected trade association. Its code linked above recognises and reflects both self-regulatory (the ICC Code) and legislative influences such as the UCP Directive 2005/29/EC as well as the Cosmetics Product Regulation 1223/2009. The great majority of major advertisers will be members of the CE, therefore it’s important at minimum to be aware of the code. Some of the more high profile/ sensitive regulatory areas are shown below (footnotes omitted); best to read the full code as it has some significant new rules on contemporary cultural issues. Also valuable is the CE September 2020 Cosmetic Product Claims Compendium which assembles applicable legislation, self-regulation, best practices and guidance and the May 2019 Guidelines for cosmetic product claim substantiation.

2.2. Social responsibility

2.2.1. General principles. All cosmetic advertising and marketing communication shall comply with general provisions, concerning:

- Denigration: cosmetics advertising and marketing communications should not denigrate any person or group of persons, firm, organisation, industrial or commercial activity, profession or product, or seek to bring it or them into public contempt or ridicule

- Discrimination: cosmetics advertising and marketing communications should respect human dignity and diversity. It should not incite or condone any form of discrimination, including that based upon ethnic group, national origin, religion (or no religion), gender, age, disability, lifestyle choice or sexual orientation

- Exploitation of credulity and inexperience: cosmetics advertising and marketing communications should not be framed so as to abuse the trust of consumers or exploit their lack of experience or knowledge.

- Humour may be used in advertising and marketing communications in such a manner that it does not stigmatize, humiliate or undermine any person, group of persons or beliefs.

- Lifestyle choices: cosmetic advertising and marketing communications should not be denigrating or judgmental regarding lifestyle choices that consumers choose to make.

- Play on fear: cosmetics advertising and marketing communications should not without justifiable reason play on fear or exploit misfortune or suffering

- Play on superstition: Marketing communications should not play on superstition

- Portrayal of gender: cosmetics advertising and marketing communications should not contain any sexually offensive material and should avoid any textual material or verbal statements of a sexual nature that could be degrading to those that associate themselves with any type of gender identity. Furthermore, advertising and marketing communications should not be hostile toward any gender identity

- Offensiveness: any statement or visual presentation likely to cause profound or widespread offence to those likely to be reached by it, irrespective of whether or not it is directly addressed to them, is not acceptable. This includes the use of shocking images or claims used merely to attract attention

- Taste and Decency: cosmetics advertising and marketing communications should not contain statements or audio or visual treatments which offend standards of decency currently prevailing in the country and culture concerned

- Violence: cosmetics advertising and marketing communications should not appear to condone or incite violent, unlawful or anti-social behaviour

- Safety and health: cosmetics advertising and marketing communications should not without reason, justifiable on educational or social grounds, contain any visual presentation or any description of dangerous practices or of situations which show a disregard for safety or health. Models used in advertisements and post-production techniques should not appear to promote a preferred body image of extreme thinness

2.2.2. Specific principles related to respect for the human being

Given the possible impact that cosmetics advertising and marketing communication may have on the self-esteem of consumers, the following should be taken into consideration when using models of any gender in advertising:

- Do not focus on bodies and parts of bodies as objects when not relevant to the advertised product

- Do not stage nude models in a way that is demeaning, alienating or sexually offensive. When using nudity, the media used and the intended as well as potential audience should be considered. This also applies to any way a model may be dressed, where this may be offensive in certain cultural contexts

Vulnerable populations

- Advertising could consider promoting the concept of hygiene and sanitary benefits of cosmetic products to children and teens, in particular sun protection products, oral care products, and cleaning products (including soap, shampoos and teenage acne coverups)

- Advertising of decorative cosmetics and perfumes should not incite children to overuse of such products

- Advertising of cosmetic products, including images, should not promote early sexualisation of young people

- Advertising in social media platforms, smartphone applications or games that children or teens may be attracted to or targeted by should be considered very carefully in terms of the effects they may have

Image honesty

Digital techniques may be used to enhance the beauty of images to convey brand personality and positioning or any specific product benefit. However, the use of pre- and post-production techniques such as styling, re-touching, lash inserts, hair extensions, etc., should abide by the following principles:

- The advertiser should ensure that the illustration of a performance of an advertised product is not misleading (see Product Claim Substantiation)

- Digital techniques should not alter images of models such that their body shapes or features become unrealistic and misleading regarding the performance achievable by the product

- Pre- and post-production techniques are acceptable provided they do not imply that the product has characteristics or functions that it does not have. For example, the following cases would not be considered misleading:

- Using obvious exaggeration or stylized beauty images that are not intended to be taken literally

- Using techniques to enhance the beauty of the images that are independent from the product or effect being advertised

The above recommendations are linked as they are relatively lengthy and also significant as this is sensitive territory for cosmetics marketing

Users should also be aware of the Media Authorities' May 2022 Guidelines for labelling advertising in online media DE / EN

The following is a ‘snapshot’ of the general rules that may be particularly relevant to cosmetics, but apply to all sectors, cosmetics included. Adjudications against cosmetics advertising may well come from general misleadingness or taste and decency rules, for example. The full rules are spelt out below under the General tab

Self-regulation

The German self-regulatory system has two SRO’s: the German Advertising Standards Council (Deutscher Werberat - DW), which deals with issues of social values and morality, safety and security, discrimination etc. via its Codes of Conduct (EN), and the Centre for Protection against Unfair Competition (Wettbewerbszentrale - WBZ) which is authorised under law to to prosecute unfair commercial practices; explanation of WBZ role here (EN)

4.1. DW General Principles on Commercial Communications (EN), also known as ‘Ground rules’ (Grundregeln). Key extracts:

Advertising must uphold generally accepted social values and prevailing notions of decency and morals. At all times, it must be based on the principles of fair competition and responsibility towards society. In particular:

- Consumer trust must not be abused and inexperience or lack of knowledge not exploited

- Children and juveniles must not be subjected to physical or psychological harm

- Discrimination in whatever form – on grounds of race, ethnic origin, religion, gender, age, disability or sexual preference, or by reducing an individual to a mere sexual object – should be neither fostered nor silently tolerated